ADVERTISING

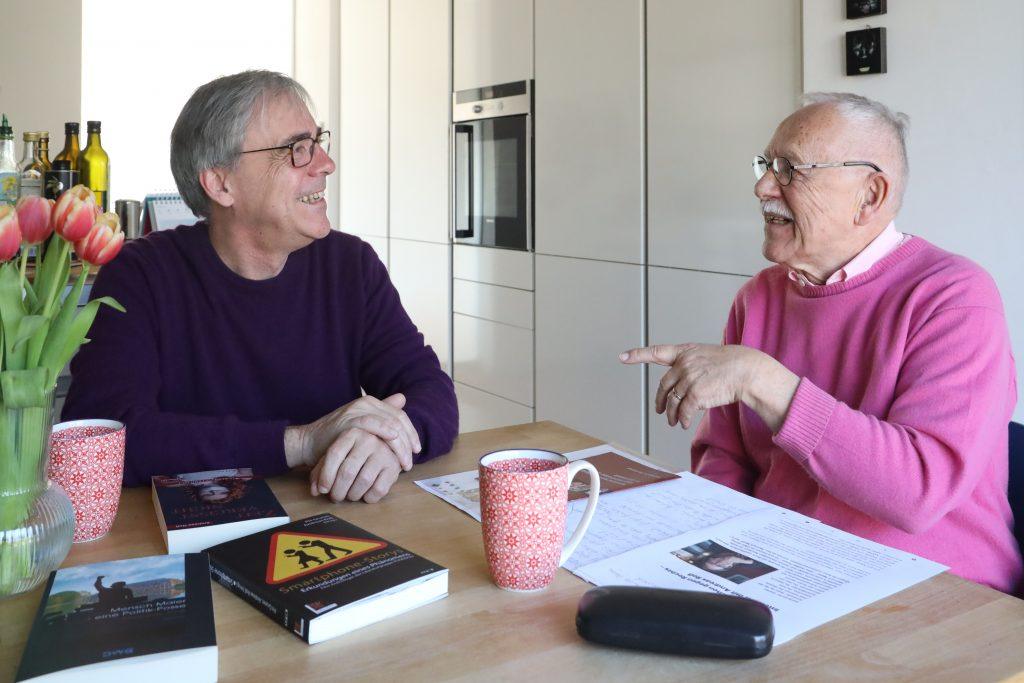

Darmstadt roundtable discussion with crime author Andreas Roß

Between 1950 and 1975, the legendary "Darmstadt Talks" event series took place, aiming to bring socially and culturally relevant topics to the forefront of public discourse. The "Darmstadt Table Talks" are intended to be somewhat less focused, giving a platform to those who contribute to the preservation and development of our society in various capacities. This time, journalist and publicist W. Christian Schmitt, along with cameraman Werner Wabnitz, are guests of Andreas Roß, a Darmstadt crime novelist.

It's safe to assume that Andreas Roß belongs to the very small circle of crime writers who have actually experienced firsthand what a police station "identification procedure" involving photos, fingerprints, and so on is really like. This happened and was staged for a column by Bert Hensel published in the Darmstädter Echo. Looking back, Roß hopes that this forensic file has long since been closed.

Photo: Werner Wabnitz

And we can begin our discussion, which starts with the seemingly simple question: Why write crime novels when everyday reality, as can be read not only in the tabloids, reflects or even anticipates everything that writers later imagine? Mr. Ross, what about you? What fascinates you, and what fascinates crime fiction readers, about murder, mayhem, and all the other horrors?

“I was socialized during my studies,” he says. Among other things, he worked at the Dieburg correctional facility. On the side of the good guys, of course. How exactly he became a crime writer can be read at the end of this article. But first, let's talk about how such a novel comes about. What it should contain. “I'm someone,” he reveals, “who is driven to his desk” because he has to put down on paper what has “grown inside me.” Prompted by external events, sometimes even “forced.” And time and again, he asks himself whether what he's about to write should actually be published. He then sets about changing what he's written so that no conclusions can be drawn about his life. Sure, there's a certain plot at the beginning, but the story develops its own way chapter by chapter. The outcome of a case often only becomes clear during the writing process.

Then I ask him how many murders he typically includes, whether the investigating detective is rather silly, and, in general, how long he works on such a manuscript. "Sometimes even a whole year," he says. But then the case is solved. The number of murders emerges during the writing process. But, I press him, have you also written crime novels where—as in real life—there was no solution? "That happens," he says. He recalls one book in which the perpetrator could not be identified.

And what about role models? As an author, do you also think about exemplary officials like Colombo, Brunetti, or Maigret and their methods when working on a new book? Of course, you've read, seen, or heard about one or two of their work, but adaptations are not an option. "I'm a storyteller," says Roß, "someone who seeks and finds his own stories." Okay, so everything is written down, but what happens next? Who—besides the editor later—checks the text for possible factual inaccuracies? Crime expert Roß explains: "I have several test readers who look very closely and who, of course, are mentioned in the acknowledgments at the end of the book." And then there's the chance to make improvements when he reads from the manuscript at readings and listeners raise their hands.

And we also discuss this in his apartment in the Martinsviertel district: Anyone who looks at the bestseller lists will discover more and more crime novels at the top. And the (remaining) newspapers are also increasingly featuring crime novels in their literary sections; the FAZ, for example, even has dedicated review pages. All that's missing is for a crime writer to be awarded the Büchner Prize soon – or has that already happened?

Finally, as promised: Here is the answer to my initial question about why he writes crime novels. Andreas Roß says it's connected to his time in Dieburg, where Peter Zingler, "a professional burglar," once spent several years in prison. This is the same Zingler who later caused a sensation (also) as a writer and screenwriter (including for "A Case for Two"). And, as Wikipedia states, he also founded the Frankfurt Novel Factory in 1985, together with, among others, "brothel owner Dieter Engel and Herbert Heckmann, the president of the German Academy for Language and Literature.".

When Andreas Roß saw, through the example of Zingler, that crime novels could be highly entertaining and enjoyable, his decision was clear. Incidentally, so was his final statement: "I've been retired since April 1st, but not inactive," he concludes.

profession

, he spent over three decades advising tenants for various housing associations in southern Hesse. During his time there, he found inspiration for his quirky stories in the long, dark hallways of aging apartment buildings. He also has a deep love for his adopted home of Darmstadt. In addition to two short story collections, he has published six crime novels, most recently the political farce "Mensch Maier." From 1996 to 2008, and again since September 2013, he has contributed monthly short crime stories to the Darmstadt magazine "Vorhang Auf!" (Curtain Up!). He is a member of the Poseidon literary group and part of the crime writers' association "Das Syndikat" (The Syndicate). Learn more about him at https://www.krimiautor-ross-darmstadt.de/

With Mayor Hanno Benz, our next interviewee, we conclude the series “Darmstadt Table Talks” after 18 episodes.