ADVERTISING

Chip innovations are becoming ever smaller and more powerful

Computer chips are the foundation of our digital world. No smartphone, no computer, no car, and no remote control can function without them. And one not-so-distant day, they will probably be implanted in our heads as well.

Artificial intelligence (AI) in particular is driving the demand for more computing power in a compact form. Chip manufacturers are reaching their physical limits in this process. European startups and universities are researching chip innovations to satisfy this growing hunger for computing power.

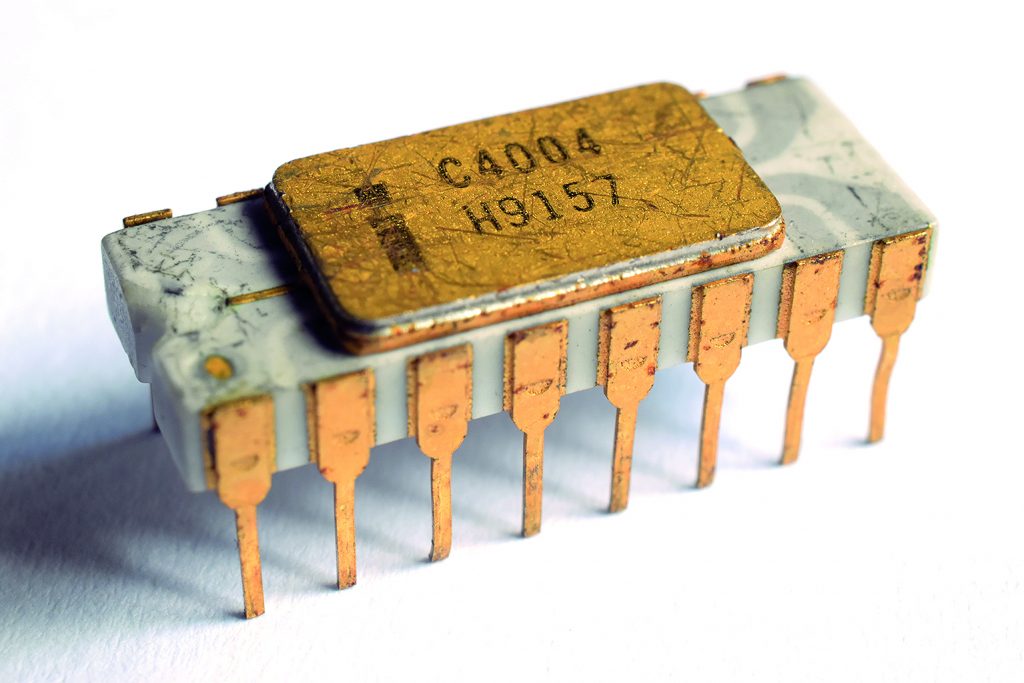

In 1971, the chip company Intel launched the first commercially successful microchip, the "4004." At the time, it was a sensation; today, however, the three-by-four-millimeter computing chip seems clunky. And above all, underpowered: it contained a mere 2,300 transistors—an unimaginable number back then, ridiculously few by today's standards.

Transistors remain the core of every computer chip. Tiny switches that toggle between on and off, between zero and one. These switches lay the foundation of our digital world. The more transistors, the more powerful the chip: and the global demand for computing power and data storage is exploding.

For years, the chip industry has been preoccupied with one question above all: How many more transistors can fit on a single chip? Over the decades, transistors have become ever smaller, so that today they consist of only a handful of atoms. These switches are now thinner than a human hair, smaller than a red blood cell, and equipped with kilometers of wiring. A tiny switch—500,000 times smaller than a millimeter—that has become absolutely indispensable in our daily lives. Two hundred million transistors can fit on one square millimeter; on a single chip, even tens of billions

However, in the near future, this attempt at shrinking semiconductor science will reach its physical limit.

Currently, we use chip technologies such as CPUs (Central Processing Units) for computers and smartphones. The alternative technology of GPUs (Graphics Processing Units), also known as graphics cards, was originally developed for images, video content, and 3D graphics for computer screens. Chip manufacturer Nvidia made a name for itself with these chips and is currently riding the wave of demand for AI chips. These graphics cards have the advantage of being able to perform parallel tasks and handle many tasks simultaneously—precisely what AI needs to work efficiently.

For AI, graphics chips have proven to be the best solution currently available; GPUs are the fallback option for AI algorithms. This is because there are simply no new approaches to AI chips at the moment. What does exist is a great deal of research and innovation. Although every nanometer on your chip is already packed with switches, there is still unused space, specifically in terms of height. This is what Semron is researching. The Dresden-based startup has developed chips that bring AI directly to end devices such as smartphones and headphones. This allows data to be processed locally on the devices, which is particularly advantageous for sensitive information. However, for the chips to be powerful enough, they must be as small, compact, cost-effective, and energy-efficient as possible

Co-founder Aron Kirschen is well aware that simply stacking three, four, or even five chips in a package isn't enough. Five times the performance, combined with the cost of five chips, is of no use when a 1000-fold increase in performance is required. Instead, Semron plans to apply multiple chip layers during the manufacturing process itself. Their patented semiconductor technology, "CapRAM," allows for the local processing of AI models. This already works with memory chips, like those found in smartphones. Our phones contain up to 200 layers of memory. However, this technique proves more challenging for processors—the computer components of a chip. Firstly, transistors aren't so easily stacked. Secondly, this design requires more energy, and at higher energy densities, the chip risks overheating. Semron claims to have solved this problem. Now the team faces the major challenge of getting chip manufacturers to implement the patented manufacturing process and produce the chips in large batches. The idea alone, however, is not enough to satisfy the ever-increasing demand for computing power. The chips also need to be manufactured – and that doesn't happen in Germany or even in Europe. It's comparable to the industrial revolution 150 years ago.